MDA: It’s not just for games anymore

MDA is a framework for analyzing games, originally developed by Marc LeBlanc of Mind Control Software. MDA stands for Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics, and is presented as a layered approach to analyzing and designing games. Creators of games come from the perspective of writing mechanics (rules), which result in some dynamics when the game is played. Players are less attached to the rules, but experience the effects of the dynamics, and this results in some sort of aesthetic experience. Marc LeBlanc developed MDA originally as a system that would allow for gradual iterative development of design, where each of mechanics dynamics and aesthetics can be examined individually. Each could be subject to analysis and design. If a particular aesthetic experience was desired, for instance, “discovery,” then the designer could work backwards and develop dynamics that would encourage feelings of discovery, and then mechanics that would generate those dynamic systems. Core to this theory is the understanding of how each of these layers interacts with the others.

Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek describe a taxonomy of several explicit aesthetic terms. The ones listed are sensation, fantasy, narrative, challenge, fellowship, discovery, expression, and submission, though the authors make clear that many more aesthetic goals are possible. What is interesting about these aesthetic goals is that they tend to be closely associated with genres (either individually, or in groups). For instance, roleplaying games tend to stronly value fantasy and narrative; casual games are frequently passtimes, so they fall under the category of submission; first person shooter games tend to be about challenge, sensation, and competition. Individual games will of course have different aesthetic goals (especially in terms of order of importance), but genre can be seen as closely tied to specific aesthetic patterns. This is the case not only in games, but in other media as well. In film (and I am speaking exceedingly generally), the romance genre is closely tied to particular emotional responses, sympathy, hope, joy; the genre of summer action movies is strongly tied to sensation and exhilaration; horror films have aesthetics of fear and suspense, often surprise. In prose fiction (and non-fiction, imaginably) too genres are still tied to aesthetics and emotions. While films and novels may be formulaic, we do not see and read them for the formulas, we enjoy them for the experience of seeing of reading. We enjoy them because we get something out of them.

In discussing film and novels specifically, it should be clear that I am talking about narrative. In doing so, it will be important to remember that narrative is bipartite, containing both (using Chatman’s terms) story and discourse. Story is the plot, the characters and events that make play out in the narrative, while discourse is how this information is presented. In text, discourse is in terms of writing, using literary techniques and devices to communicate, while in film the discourse is a visual language. The most clear way of looking at narrative in terms of mechanics is structurally or formally, where both the story and discourse must obey a set of rules to fall within a genre. This approach tends toward narratives whose plots obey certain formulas, often culminating in three or nine part structures. This approach is often used for analysis of narratives, and is used in writing, but primarily in terms of making sure that the written narrative has a suitable structure. However, there is a dimension missing: structural analysis misses the dimension of dynamics. While we enjoy narratives for the experience of them, we require the structures to be played out. Structures alone cannot be played out, though. It is necessary to rethink the ideas of mechanics and dynamics as apply to narratives, then.

Dynamics are about playing out, about the execution of a system over time. We feel pleasure in reading about the downfall of the villian or the struggles of the hero in an adventure story not because they fall within specific generic rules (although there is probably some satisfaction that has to do with familiarity), but because of the feelings that the villian deserves what he gets, or because of sympathy with the hero. The fact that these fit into a structure or monomyth is not enough to explain why they move us, we must look closely into why we feel these things. I suspect that it is because of simulation: the villian’s downfall is not satisfying unless we feel that the villian deserves the downfall, and that he deserves it because of whatever awful thing he did early on. The reasoning between these points is not structural, but causal, and furthermore causal at an emotional level. Keith Oatley theorizes that fiction is literally software that we simulate in our minds. To understand dyanmics in narrative, it is necessary to treat the story as taking place in time, within a world. The presentation of time need not be linear, but the reader still understands the narrative by making causal connections. The study of dynamics within story worlds is complicated by the fact that stories are usually linear, and we rarely see branches that reveal the changing dynamic structure of the story world. In a mathematical sense, the dynamics are under specified by the story contents. This underspecification need not be a problem, though. Actual narrative structure itself is underspecified, but readers make sense of incomplete elements of narrative by mentally filling in the blanks. For instance, in Pride and Prejudice, the first line of dialogue occurs between Mr. and Mrs. Bennett, but the conversation is not contextualized in terms of where or when it occurs, whether the other family members are there, or any other detail. Readers have no trouble processing this, though, and may supply differing interpretations of what these circumstances might be. Each of these interpretations is valid, and can be considered acceptable. The author may even imagine details, but intentionally leave them out, in the interest of succinctness. The study of the dynamics of story worlds is supplemented by examining other works within the context of source, for instance, other works by the author, contemporary works, or derivations. These can give the extra context needed to understand the shape and structure of dynamics, and enough perspective to see the alternate ways that events might play out that might have diverged from the course of the original narrative.

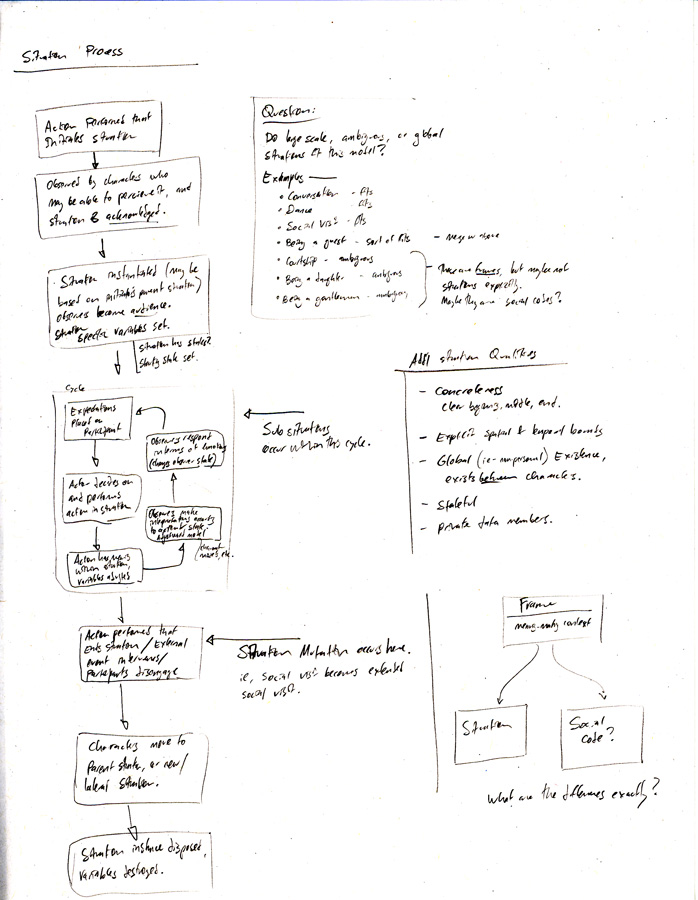

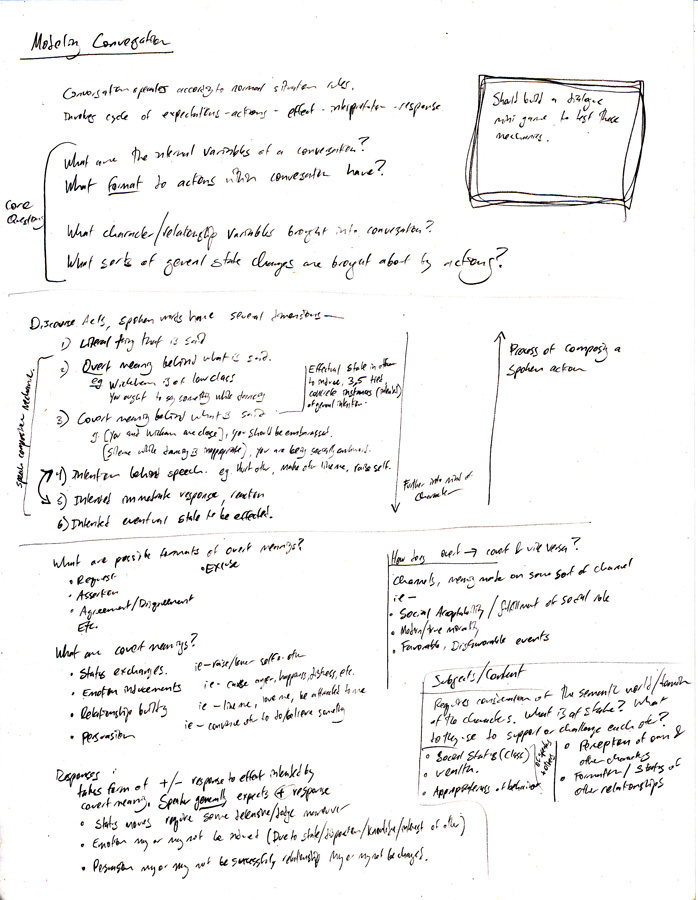

The dynamical systems of narratives are probably going to at first look quite different from the dynamical systems in games. The element to remember with these is that they are about the systems and trends that emerge from the fluctuation of state. So for instance, in love stories, a dynamical element would be the rising and falling affections between characters, changing relationships, and the progression along the spectrum of courtship. The mystery genre is actually well suited to a game-like analysis of dynamics (because they can be compared to the dynamics of mystery games); these are about the gradual acquisition of evidence, mounting tension and suspense, and evaluation and analysis of characters. Dynamics feature changing variables, and describe the space wherin the world (or the reader’s understanding of the world) changes. It is important to note though, that these are explanations of generic dynamics of genres, and actual works and authors usually feature more precise dynamics. For instance, Jane Austen uses an aesthetic of irony, and one way this is expressed dynamically by having indirect commentary on the actions and values of some characters. This is a dynamic not in the change of the world, but in how the reader percieves it. Austen also dynamically expresses her irony by having characters clash according to juxtapositions of moral values. The actual moments that deserve commentary, and the moral orders that clash are part of the mechanics.

Mechanics are the rules by which things happen, the rules by which effect follows from cause. Where dynamics are changing systems, the mechanics are the means of change that occurs in those systems. The relationship between mechanics and dynamics is heavily derived from simulation. Exactly what makes up the mechanics is hard to figure out in terms of narratives. Novels are based in realism (in terms of individual focus and detail), but the story worlds defined still operate according to specific rules. For instance, Ann Radcliffe’s gothic villians would not be at all appropriate for Austen’s story worlds. The male-centered perspective of Tom Jones would not work in a domestic feminine narrative such as any of Jane Austen’s works. A bloody climax such as one found in Shakespeare would similarly not make sense in any of Austen’s story worlds. So, setting, perspective, and types of events all inform the types of worlds that may follow from different narratives. These are all static elements, they are not dynamic, but they shape dynamics. These elements are thus part of the mechanics. Like the matter of interpreting dynamics, though, mechanics must be interpreted in narrative. They are not determined, and must be reached through an analysis and reading of the text. The process for extracting mechanics is something that deserves an immense degree of attention, but is outside the scope of this document.

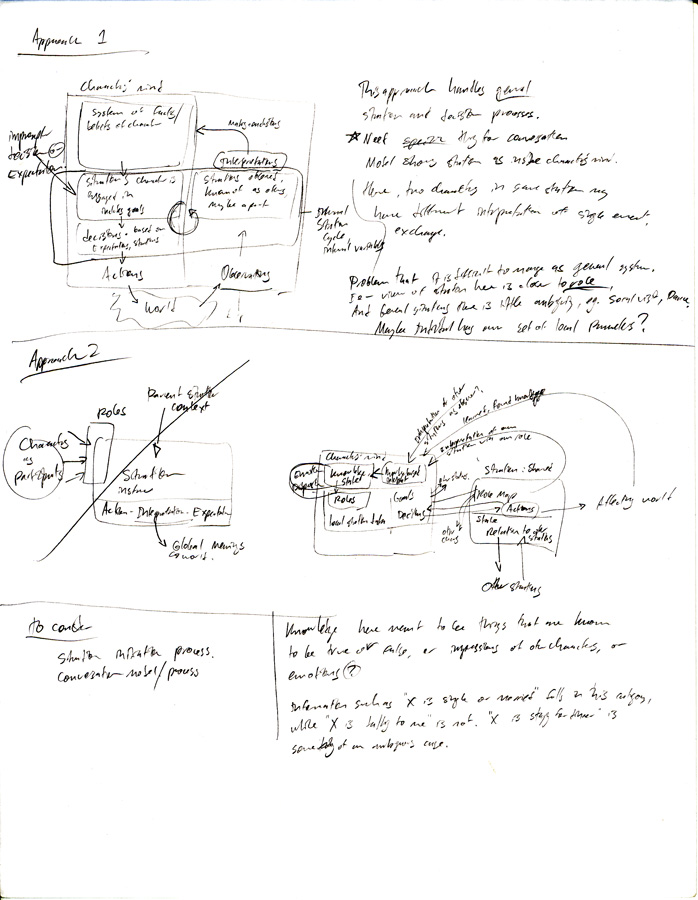

I believe that the primary dynamics in Austen’s works are social. The means of interaction are social, and the subject material and changing values are social relationships. To determine the mechanics, then, I would suggest turning to the prodigious field of social interactions, namely sociology, and particularly symbolic interactionism. Symbolic interactionism is useful for examining interactions as taking place on a symbolic plane, a space well handled by a game interface (furthermore one which has support in existing games, eg, The Sims).

Generally, the study of mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics can be applied to narrative media just as well as games.